Collage of Found Objects by Salley McInerney

Collage of Found Objects by Salley McInerney

In the truck, Mike and Nita bickered, and it was grating on Katy’s nerves.

“He doesn’t have insurance. We will have to step up.” This from Mike. He always drove by default. Nita had never learned to drive; she didn’t have the temperament for it.

“I brought my checkbook,” Nita answered.

Nita always had her kids call her by her first name. The way she saw it, if any of them needed her, she would hear her own name being called. Hearing a child yell “Mom” on a playground or a beach just got lost in parental white noise.

“You know how much he hates Fountain Valley! No way we’re letting them do anything major for him there…”

“I remember,” Nita mumbled. “He made us promise after that bruised tailbone when we moved.”

“Will you two stop!? For all we know, he might be dead!” Katy exploded, shocking herself.

It was out there, and there was no way to take it back now. Katy mentally cursed all the recalcitrant street lights that kept slowing their momentum. At age twenty-four, wisdom and patience were not her bragging points.

Mike eventually parked the battered work truck in the emergency lot. Katy, sitting in the middle seat, could only wait. Nobody seemed to be in a rush.

Katy studied her mother’s profile in the parking lot lights. Nita always made her think of one of her favorite actresses, Jane Darwell. Here, in the deep shadows of the old work truck, Nita fully encapsulated all the heart and soul of one of the greatest, strongest matriarchs of all time: Ma Joad from The Grapes of Wrath. Nita had seen some shit. She had survived the Great Depression, spent World War II in a factory doping airplane wings.

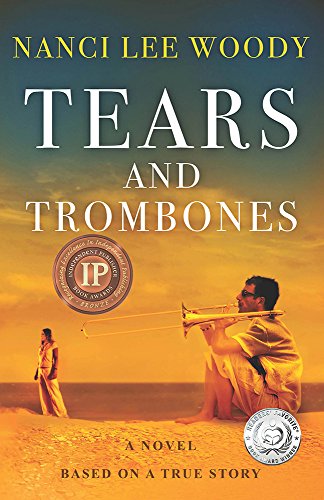

Persimmon Tree readers will love young Joey’s mother, Ellie, as she navigates through poverty and around a philandering, alcoholic husband to help her boy achieve his dream of becoming a classical musician. She scrimps and saves enough to take her nine-year-old boy to the San Francisco Symphony to hear Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, though she herself had never before set foot in a concert hall.

Readers will follow Joey through his childhood with its real-life pain, and watch as he, too, navigates around his father and uses his creativity to passively “get even” for his dad’s cruelty, always knowing his mother will be there to rescue him. Though their relationship is not without its trials, she models for him loyalty, persistence and hard work and allows no excuses when times are hard.

In high school Joey falls quickly and deeply in love with a curly-haired beauty, and is torn between his love for her and pursuing his musical dream. When another girl courts him and offers to help him pay his way through college and music lessons, Joey marries her, thus forming a tormented triangle love affair.

You will follow Joey as he auditions for the Sacramento Symphony and Music Circus. You will be there with him when he plays his horn with Frank Sinatra, studio musicians from Hollywood, The Beach Boys, Dorothy Dandridge and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison.

Having achieved his musical goal, will Joey ever be able to set his personal life right?

Nanci's short stories and poems have been published in The California Writers Club Literary Review, a CWC Anthology, October Hill Magazine, The Fault Zone, the Sacramento Poetry Society’s Tule Review, Your Daily Poem, The Monterey Poetry Review, the Haight Ashbury Literary Journal and many other online and print publications.

Check out Nanci’s website for samples of her writing and art, click here to listen to the music in Tears and Trombones, and watch for Nanci’s new book of poetry coming out this fall.

Available on Amazon

Persimmon Tree readers will love young Joey’s mother, Ellie, as she navigates through poverty and around a philandering, alcoholic husband to help her boy achieve his dream of becoming a classical musician. She scrimps and saves enough to take her nine-year-old boy to the San Francisco Symphony to hear Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, though she herself had never before set foot in a concert hall.

Readers will follow Joey through his childhood with its real-life pain, and watch as he, too, navigates around his father and uses his creativity to passively “get even” for his dad’s cruelty, always knowing his mother will be there to rescue him. Though their relationship is not without its trials, she models for him loyalty, persistence and hard work and allows no excuses when times are hard.

In high school Joey falls quickly and deeply in love with a curly-haired beauty, and is torn between his love for her and pursuing his musical dream. When another girl courts him and offers to help him pay his way through college and music lessons, Joey marries her, thus forming a tormented triangle love affair.

You will follow Joey as he auditions for the Sacramento Symphony and Music Circus. You will be there with him when he plays his horn with Frank Sinatra, studio musicians from Hollywood, The Beach Boys, Dorothy Dandridge and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison.

Having achieved his musical goal, will Joey ever be able to set his personal life right?

Nanci's short stories and poems have been published in The California Writers Club Literary Review, a CWC Anthology, October Hill Magazine, The Fault Zone, the Sacramento Poetry Society’s Tule Review, Your Daily Poem, The Monterey Poetry Review, the Haight Ashbury Literary Journal and many other online and print publications.

Check out Nanci’s website for samples of her writing and art, click here to listen to the music in Tears and Trombones, and watch for Nanci’s new book of poetry coming out this fall.

Available on Amazon

When Katy was a baby, Nita’s eccentricities made her the neighborhood scapegoat. Her kids were taken away; she was incarcerated for psychiatric review. Could she be entrusted with their return from foster care? When the doctor’s reports were read in court, the judge decreed: “This woman poses no threat to herself or others. Give her back her kids. Case closed.”

Katy led the way to the reception area and announced their arrival. A nurse escorted them to an empty room across the hall. The nurse made sure they were each seated and said she would bring the doctor in a moment. Katy had a real bad feeling about this. It was confirmed when the nurse returned, opening a large box of real Kleenex.

You don’t see the real thing in hospitals, Katy thought. They usually give patients the miniature cheapie tissues that look like they came from a kid’s playhouse.

The doctor sat on his wheeled stool. First, he addressed Mike.

“Are you his brother?”

“Yes.”

Then he moved over in front of Katy.

“Are you his sister?”

“Yes, and I’m an organ donor, if it helps.”

The doctor then sidled over to face Nita. It was as if he were culling her from the herd.

“And are you his mother?”

“Yes,” a bare whisper.

Katy was stricken at Nita’s stoicism. Everybody must have known what was coming next. The doctor took a long glance at his clipboard.

“I’m sorry to have to tell you this, but your son, Neil, has passed away tonight.”

Nita’s eyes were closed, but Katy and Mike shared shocked stares, their mouths agape.

“His name,” Nita corrected, “is Noel.”

Author's Comment

We all have messages that are important to share. Light. Heavy. Hopeful. Tear jerkers. Please share your own. Fictionalize them if your privacy is sacrosanct.Don’t listen to your inner critic; someone needs to see or hear your message. Mine are at katywrightgallery.com.

Katy Wright's parents were freethinkers. Her formative years were spent alongside the barrio and the railroad tracks in Santa Ana, CA.

Katy Wright's parents were freethinkers. Her formative years were spent alongside the barrio and the railroad tracks in Santa Ana, CA.

As a child growing up in the 1960s, Salley McInerney was drawn to the “junk” people put out in the street for the “trash man” to collect. As an adult, she turned her fascination with found objects into art, creating images using screws, washers, bottle caps, flattened tin cans. She graduated from the University of the South, studied art at the Fenland School of Crafts, and lives in Camden SC. When not in her studio, she is riding horses.

As a child growing up in the 1960s, Salley McInerney was drawn to the “junk” people put out in the street for the “trash man” to collect. As an adult, she turned her fascination with found objects into art, creating images using screws, washers, bottle caps, flattened tin cans. She graduated from the University of the South, studied art at the Fenland School of Crafts, and lives in Camden SC. When not in her studio, she is riding horses.

I absolutely loved the art for this story.