I would do anything for him—anything except dissect a frog, a requirement of biology class. My friend Sam stepped in for me when we were called upon to perform the dissection. I was grateful to Sam for this.

One morning, Mr. Kaufman stopped at my desk and said, “Please come see me at the end of the day.” Sam shot me a look, but I did not meet his gaze. He was not happy about my feelings for Mr. Kaufman.

Somehow, I made it through the endless hours of French, history, and algebra. At 2:45, the final bell rang. I walked down the long hall and stood in the doorway of Mr. Kaufman’s cubicle. There were stacks of books and papers everywhere, except on one bookshelf filled with a huge pothos plant.

“You can’t kill those plants,” I said. “My mother has one. It just grows and grows.”

“That’s true. I’ve had this one for five years,” Mr. Kaufman said, as he transferred books from one chair to another. “Have a seat. How are your classes? How do you like being in the chorus?”

He knew that I took chorus. That meant he had been checking my schedule. “Classes are fine and I love singing. I’m an alto.”

He nodded. “Alto, that’s great. But are you working too hard? You look extremely thin. Are you eating enough?”

“I don’t have much time to eat when I’m working on extra credit assignments. The Scientific American articles are really hard. I sit for hours in the library, reading and taking notes, and sometimes, I just forget to eat.”

“Why?” said Mr. Kaufman

“Why do I forget to eat?”

“No, why are you torturing yourself with those journals?”

“To impress you,” I said, not sure if I had spoken the words out loud.

He leaned back in his chair. “You have impressed me, but there’s no need to work so hard. You’re young, you’ve got lots of time. Pace yourself. Do you see what I mean?”

“Not really,” I murmured. His eyes were deep blue. I twisted the chain of my heart locket. It was the kind that opened. You could put a picture in it, but I hadn’t yet. “Are you going to send me to the guidance counselor?”

“I don’t think that will be necessary,” Mr. Kaufman said.

“Are you going to call my mother?”

He tugged at his tie. “Only if you’d like me to.”

“I don’t think that will be necessary,” I said, and he smiled. I loved how he looked when he smiled. In class, he was always so serious when he taught us about lysosomes and mitochondria.

He placed both hands on the desk and leaned towards me. “Here’s the deal. No more extra credit. Your class work is exemplary, except for that frog business. I’d like you to check in with me from time to time so I know you’re eating enough and that you’re OK….”

I wanted to say, “When should I check in? How? How often?” but I kept quiet. I stood up, and Mr. Kaufman stood up, too. He extended his hand across the desk but I didn’t dare take it.

And as I walked down the hallway, his voice echoing in my head, I was gripped by a hunger so strong that I feared I might never be satisfied.

Author's Comment

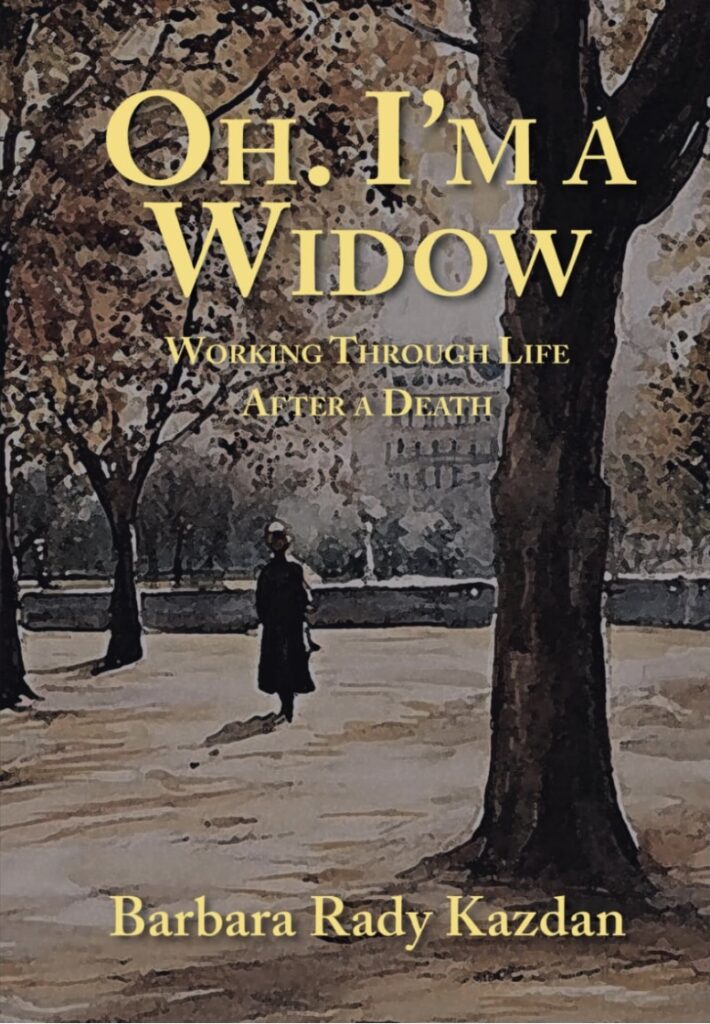

Sometimes stories simmer in my mind for years or even decades. For “Hunger,” I reached back in time to find my voice at age fourteen. I wanted to dwell in the world of reality suffused with fantasy where teenagers live, unbeknownst to their parents and teachers, a hazy world filled with confusion and also redemption. It began, as these things often do, with a question that was never answered. A husband of forty-two years, gone in the blink of a December morning. The house, once filled with the scent of coffee and the rustle of newspapers, now echoing with silence. She was alone. But not defeated.

She didn’t crumble. She called Kay. Kay brought her knitting.

Barbara, a woman who once ran nonprofits with the precision of a Swiss watch, now found herself staring down furnace filters and frozen faucets. She wore grief like a vintage trench coat—heavy, but tailored. She joined a grief group. She learned about ‘widow fog’. She Googled ‘how to cover outdoor spigots’. She did it herself.

She missed her husband. She missed her job. She missed being asked, “What do you do?” and having a damn good answer. So she wrote. Essays at first. Then this book.

She tried online dating. She met men who smelled like old upholstery and talked only about themselves. She kissed frogs. She stayed single. She liked it that way.

She found friends. Not all at once. Not easily. But she found them. A memoir group. A book club. A neighbor who said, “Lunch Tuesday?” and meant it.

She planted a tree in her husband’s memory. It leaned. It bloomed. So did she.

And in the end, she didn’t just survive widowhood. She redesigned it. With grace. With grit. With a pen in one hand and a dog leash in the other.

Available from Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, and your local independent bookseller.

It began, as these things often do, with a question that was never answered. A husband of forty-two years, gone in the blink of a December morning. The house, once filled with the scent of coffee and the rustle of newspapers, now echoing with silence. She was alone. But not defeated.

She didn’t crumble. She called Kay. Kay brought her knitting.

Barbara, a woman who once ran nonprofits with the precision of a Swiss watch, now found herself staring down furnace filters and frozen faucets. She wore grief like a vintage trench coat—heavy, but tailored. She joined a grief group. She learned about ‘widow fog’. She Googled ‘how to cover outdoor spigots’. She did it herself.

She missed her husband. She missed her job. She missed being asked, “What do you do?” and having a damn good answer. So she wrote. Essays at first. Then this book.

She tried online dating. She met men who smelled like old upholstery and talked only about themselves. She kissed frogs. She stayed single. She liked it that way.

She found friends. Not all at once. Not easily. But she found them. A memoir group. A book club. A neighbor who said, “Lunch Tuesday?” and meant it.

She planted a tree in her husband’s memory. It leaned. It bloomed. So did she.

And in the end, she didn’t just survive widowhood. She redesigned it. With grace. With grit. With a pen in one hand and a dog leash in the other.

Available from Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, and your local independent bookseller.

Robin Mayer Stein started writing at age five and never stopped. She grew up in Jackson Heights NY, and moved to Boston to attend law school. Her work has appeared in Home Planet News, Fiddlehead Folio and the new renaissance. She received a poetry grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. She speaks at schools and libraries about her book, My Two Cities: A Story of Immigration and Inspiration. She loves sharing stories with Stella, Maya, and Liam, her grandkids.

Robin Mayer Stein started writing at age five and never stopped. She grew up in Jackson Heights NY, and moved to Boston to attend law school. Her work has appeared in Home Planet News, Fiddlehead Folio and the new renaissance. She received a poetry grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. She speaks at schools and libraries about her book, My Two Cities: A Story of Immigration and Inspiration. She loves sharing stories with Stella, Maya, and Liam, her grandkids. After forty years in finance, Linda K. Allison is enjoying life as a writer, photographer, and explorer. Her work has appeared in Bright Flash Literary Review, 2023 Utah’s Best Poetry, Pose Anthology, and others. Her photography has appeared or is forthcoming in Burningword Literary Journal, The Sunlight Press, and others.

After forty years in finance, Linda K. Allison is enjoying life as a writer, photographer, and explorer. Her work has appeared in Bright Flash Literary Review, 2023 Utah’s Best Poetry, Pose Anthology, and others. Her photography has appeared or is forthcoming in Burningword Literary Journal, The Sunlight Press, and others.

I like the concise combinations of two: Sam/Mr. Kaufman, no hunger for food with hunger for romance, pothos at home and in Kaufman’s office, playing with the locket/necktie. Thank you.