At the school, faculty members got a five-year review of their teaching, scholarship, and community service, regardless of whether they had tenure. I’d decided to retire before my next review but told no one. That knowledge let me spring a surprise on folks in those corseted corridors.

For less than three dollars, I bought a box of children’s face paints. The six colors— red, yellow, blue, green, black, and white—proved enough for my purposes. I pulled the box out of a desk drawer every morning and painted my face before teaching. The school had rules to discourage novelty, but in it had failed to regulate face-painting.

I went to town. A bolt of lightning slashed down my cheek one day. A heart beamed from one cheek the next day. I painted a night sky, complete with stars and a quarter moon, on my forehead another time. A red question mark in the middle of my forehead garnered the most stares.

Students’ reactions held some surprises for me. I learned that a painted face trumped a brown skin when it came to their perceptions. The flowers and goldfish took them by surprise, threw off their expectations. The bees and spiders on my face swept away, or at least suspended, preconceptions. My students could take me in with less racial garbage. We had a straighter shot at connection.

The images also let me add sauce to the vocabulary I served up in Spanish 101. Few of my students forgot the meaning of bombilla after seeing the yellow lightbulb outlined in black on my forehead.

My two-dollar box of paints also helped me address the broader issues of college life. It provided a platform on which to stand against the frequent life-sapping grayness of academia. College teaching and learning rank as serious business, but they need not bury one alive.

I admit that I relished hard looks from some administrators because I knew my retirement plans put me beyond their reach. Faculty meetings seemed less poisonous when I joined them with a giant sunflower painted on my left cheek.

Yes, I savored the disapproval of those two years, but also the fun. One day, I painted my nose black and drew whiskers and a ruff on my face. A student asked, “Que pasa con la cara?”

“It’s International Cat Day,” I replied, “and I’m celebrating.” Only later did I learn that there is indeed such a holiday.

The face painting drew me closer to my students, who anticipated fun and, one told me later, bet on what I’d paint next. After years shrouded in grayness, my paint box also gave me a foretaste of rainbows that could come my way with retirement.

“Duke sauntered across the schoolyard, dragging his feet in the dirt. When he got to the fence on the other side, he slowly turned around, as if afraid of what he might or might not see. I waved. He stared back.”

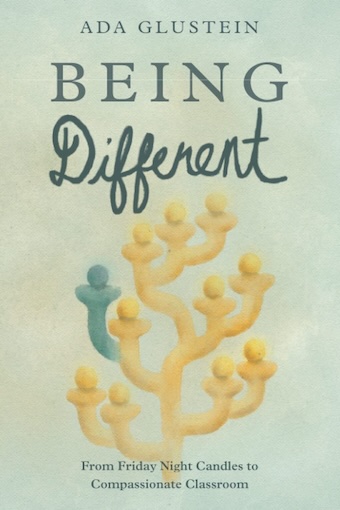

The heart-catching stories in Ada Glustein’s memoir, Being Different, tell a universal story about feeling different and longing to belong. She recounts tales of growing up in a Jewish immigrant family during and following World War II, and the experiences that stand out during her school days, not knowing how to fit in to the world beyond home. She reflects on her years of teaching diverse children who also experienced life as “different.” With her deep understanding of the importance of belonging, as seen through her own eyes and through the eyes of the children she encounters, she finds her own sense of belonging through helping those children find theirs.

Ada’s stories are told with humor and pathos: spilling the wine at her family’s Passover seder; slamming down her books when provoked by one of her Masters at teacher’s college; barely holding in her laughter at the antics of the woman who is housing her during her teaching practicum in a rural school; realizing that she has not included the right flesh color for one of her students to make his self-portrait; clutching three barefoot children outside in a blizzard, while waiting for the alarm bells to stop ringing; and, befriending the class bully to help her know that she, too, is an accepted and valued class member.

These stories remind us to embrace the visible and the invisible differences we all share as human beings on this planet.

Available from Amazon.

“Duke sauntered across the schoolyard, dragging his feet in the dirt. When he got to the fence on the other side, he slowly turned around, as if afraid of what he might or might not see. I waved. He stared back.”

The heart-catching stories in Ada Glustein’s memoir, Being Different, tell a universal story about feeling different and longing to belong. She recounts tales of growing up in a Jewish immigrant family during and following World War II, and the experiences that stand out during her school days, not knowing how to fit in to the world beyond home. She reflects on her years of teaching diverse children who also experienced life as “different.” With her deep understanding of the importance of belonging, as seen through her own eyes and through the eyes of the children she encounters, she finds her own sense of belonging through helping those children find theirs.

Ada’s stories are told with humor and pathos: spilling the wine at her family’s Passover seder; slamming down her books when provoked by one of her Masters at teacher’s college; barely holding in her laughter at the antics of the woman who is housing her during her teaching practicum in a rural school; realizing that she has not included the right flesh color for one of her students to make his self-portrait; clutching three barefoot children outside in a blizzard, while waiting for the alarm bells to stop ringing; and, befriending the class bully to help her know that she, too, is an accepted and valued class member.

These stories remind us to embrace the visible and the invisible differences we all share as human beings on this planet.

Available from Amazon.

Constance Garcia-Barrio, a native Philadelphian, writes a monthly column called “City Healing” for Grid, a Philly publication devoted to sustainability and social justice. She won a magazine journalism award from the National Association of Black Journalists for a feature on African Americans in circus history. Her current novel, Blood Grip, based on Philly’s Black history, is jam-packed with adventure, has a dash of romance, and a half-drunk Greek chorus.

Constance Garcia-Barrio, a native Philadelphian, writes a monthly column called “City Healing” for Grid, a Philly publication devoted to sustainability and social justice. She won a magazine journalism award from the National Association of Black Journalists for a feature on African Americans in circus history. Her current novel, Blood Grip, based on Philly’s Black history, is jam-packed with adventure, has a dash of romance, and a half-drunk Greek chorus.

Indu Varma is a New Brunswick based multi-media artist. Born and brought up in India, she immigrated to Canada in 1969. After a teaching career of 37 years, she pursued her interest in art by enrolling in the visual arts program and graduated with a degree from Université de Moncton in 2016. Based in Sackville, New Brunswick, she paints, creates ceramic sculptures, and does printmaking at Salt Marsh Studio. Her Indian heritage and Indian culture are very much a part of her Indo-Canadian identity. Her Indian roots are reflected in practically every aspect of her life, and her art.

Indu Varma is a New Brunswick based multi-media artist. Born and brought up in India, she immigrated to Canada in 1969. After a teaching career of 37 years, she pursued her interest in art by enrolling in the visual arts program and graduated with a degree from Université de Moncton in 2016. Based in Sackville, New Brunswick, she paints, creates ceramic sculptures, and does printmaking at Salt Marsh Studio. Her Indian heritage and Indian culture are very much a part of her Indo-Canadian identity. Her Indian roots are reflected in practically every aspect of her life, and her art.

Oh wow! This is so great. You are courageous Constance! Kudos to you!

I love this piece! Such creativity! I can imagine the planning and smiling along the way. “savouring the disapproval and the fun…” Love it!